The company tries to update its Princess franchise for today’s girls by focusing on inner strength rather than appearance.

At a time when the United States is getting ready to elect its first female president, the notion of the classic Disney princess—a helpless beauty patiently awaiting her prince—seems hopelessly outdated.

Disney seems to realize as much (or is at least willing to pander to critics). To fight accusations of contributing to body image problems among young girls and studies showing that the Disney Princess brand encourages gender stereotypes, Disney has issued a 10-point guide for the modern princess—and none of them has to do with tiaras or happily ever afters. The Disney Princess is getting a makeunder.

A $3 Billion Gamble

Disney’s Princess franchise dates to the early 2000s, when a newly hired executive named Andy Mooney noticed that young girls were dressing up as princesses—not Disney-specific royals, but generic ones—to attend a Disney on Ice show. Soon after, with no focus group testing and little marketing to speak of, the princess franchise launched. It consisted of coordinated products for a starting group of nine characters and has grown to become one of the company’s most lucrative enterprises—estimates put its revenue at more than $3 billion globally (compared to $300 million in 2001). The Princess franchise includes classic characters like Snow White and Cinderella as well as contemporary characters like Mulan and Merida.

The Modern Princess

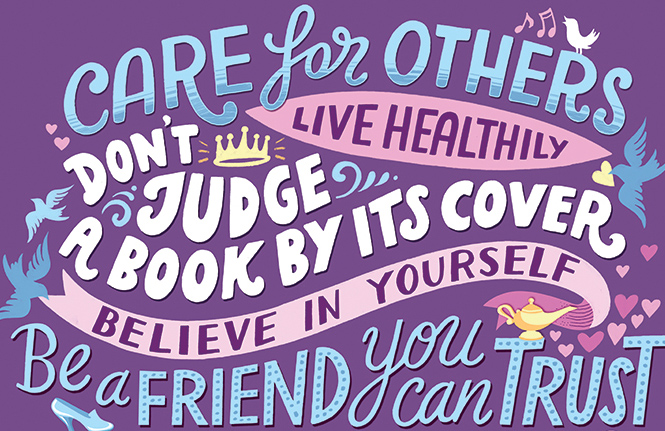

This new list of a modern princess’s aspirations focuses on inner strength and morality rather than tiaras. Commandments includes “be honest,” “don’t judge a book by its cover,” “try your best,” and “believe in yourself.”

The company asked three British illustrators to turn the tenets into typographic posters that are free to print or pick up in Disney stores and come with instructions for framing and hanging.

It’s an attempt to get into the rooms of little girls with a less stereotypical message—though it’s unclear how the principles will impact Disney’s products; the company continues to sell a multitude of pink-and-purple products that encourage domesticity and focus on physical appearance.

Illustrating The New Principles

“It seems like a really nice idea to visually show them that it’s not all about pretty dresses and handsome princes,” says the illustrator Kate Forrester. She says that she deliberately tried to avoid any suggestion of what she called “the long blonde hair stereotype,” focusing instead on fun lettering that would appeal to any young girl (or boy).

Another illustrator, Kate Moross, said she tried to include as many details as she could, because that’s what she’d always enjoyed looking at posters and art as a kid. “I like to think that anyone big or small could relate to them and they’re not just for girls but for boys too, and everyone in between,” says Moross. She didn’t identify with the Disney princesses growing up, but thinks that this project is moving them in a better direction.

Rose Blake, the third illustrator who contributed to the project, thought the new “princess principles” were spot on—she was pleased that “marry a prince” wasn’t on the list. She did have one request for Disney. “I would like to see [a princess]with a bob haircut, like me,” she says. “When I was a kid I wasn’t interested in Disney princesses at all. I liked Robin Hood, The Rescuers, the tomboy thing. It’d be cool to have a real tomboy one, like the girl in Stranger Things.”

A Business Case

With more and more pushback against the blue and pink aisles in toy stores and growing awareness of how toys can impact a child’s development, Disney has every incentive to adapt the Princess franchise to the times. It already has proof that it can market a strong female protagonist in Elsa, the complex heroine of Frozen, which has raked in over $1 billion worldwide. Meanwhile, another classic toy brand, 57-seven-year-old Barbie, has struggled to modernize—and has suffered financially as a result.

[All Images: via Disney]

This article first appeared in www.fastcodesign.com