5 Reasons Marketers Have Largely Overlooked Generation X

A few weeks ago, Lincoln Financial began running a 60-second spot about fiscal planning for your family’s future. Financial services ads aren’t typically attention grabbers, but there was something stark and penetrating about this one. Created by FCB and shot in black and white with a backing track of “Love Me Tender,” the spot showed people in their 40s, dealing with the joys and challenges of middle age—raising children, caring for elderly parents, trying to carve out time for themselves. Love, the ad said, means having responsibility—your responsibility.

If you happened to notice this spot, and if it happened to speak to you, it also may have shaken you from a kind of cultural torpor. The ad was targeted squarely at Generation X, consumers who fall between their mid-30s and mid-50s. And that’s an age group that’s not used to being marketed to very much.

These days, nearly any brand you can think of is tripping over itself to reach millennials—and leapfrogged the generation before them. It’s a situation that frustrates FCB’s chief strategy officer Deb Freeman. “I’m a proud, card-carrying Gen Xer,” she says. “We were the crossroads generation, and we had to absorb so much change—everything from growing up with technology to having no job security. We’ve been at the forefront of all that, and we’re stronger. Millennials haven’t had to fight the fight that we had. I’m so tired of hearing about the millennial spirit.”

Her pique is well founded. Demographers consider Gen X to be a “middle child”—bookended and lost between the bigger and louder cohorts of boomers and millennials. And just as middle children often feel neglected by their parents, Generation X has been disproportionately overlooked by brands and marketers, it would appear. A piece last year by the consulting firm Centro noted that “few marketers seem to be focusing on the demands and needs of this generation.” Dan Schawbel, partner and research director at the consulting firm Future Workplace, has written that Generation X is “typically forgotten by the media.” And a recent white paper from NAS Recruitment concluded that Gen Xers “have been overlooked and underestimated for a long time.”

The numbers tell the story. Last year, CNBC analyzed a large sample of companies’ earnings calls with Wall Street analysts. In 17,776 transcripts reviewed, companies mentioned Generation X just 16 times. While executives gave millennials plenty of love, the network noted, “companies do not seem to pay much attention to Gen X at all.”

The question is, why don’t brands seem to care about Gen X? As it turns out, there are several reasons.

Gen Xers came into the world between 1965 and 1982—and by all accounts, got a pretty raw deal in their youth. They were more likely than any preceding generation to grow up with divorced parents. (The national divorce rate peaked in 1980, when most Xers were barely into their teens.) Xers also came of age in an analog world, then had to scramble to catch up at the dawn of the digital age. Perhaps most notable, Xers started their careers at a time when pensions were disappearing, jobs were heading offshore, and the stock market crash of 1987 ushered in a recession. The result was a generation that grew up cynical, angry and profoundly insecure—or so goes the common perception.

“When Gen X first started making noise, they were labeled as slackers, and that stuck in the minds of companies,” says author and marketing consultant Rieva Lesonsky, who runs the content company GrowBiz Media. Inaccurate and unfair as that stereotype may be, she adds, it was the one that stuck. “Even when Gen Xers proved they weren’t slackers, nobody ever gave them another label, and nobody’s paid them any respect at all,” she points out.

In time, Gen X’s loser status would be cemented into the culture via grunge music, the suicide of Kurt Cobain and movies about spoiled wastrels like The Breakfast Club, Fast Times at Ridgemont High and Singles—a film Lesonsky describes as “just a bunch of angry and lazy people not doing anything. It was a stupid movie and made no sense, but it defined the generation.”

Did it ever. A 2011 piece in the Journal of Behavioral Studies in Business suggests that those negative stereotypes made it all the way to academia. “These latch-key children grew up quickly, experiencing rising divorce rates and violence,” it reads. To Gen X, “nothing is permanent … they are pessimistic, skeptical, disillusioned with almost everything and are very questioning of conventionality.” Why would any brand marketer want to target such a group?

While the slacker label might not have been fair, there’s no denying Gen X makes up a comparatively small segment of consumers. Pew Research counts 77 million boomers and 83 million millennials—two generations marketers have long viewed as ripe for targeting. By contrast, there are only 65 million Xers.

This is attributed to two factors. First, birthrates declined just as Generation X began (hence the moniker “baby busters”). But Gen X is also smaller by virtue of a demographic glitch nobody can really explain. “The boundaries of Generation X have not been defined by them but by the generations they’re bookended by,” observes Paul Taylor, author of The Next America: Boomers, Millennials and the Looming Generational Showdown. Taylor explains that because the U.S. Census fixed the last year of the baby boom at 1964 and because most agree that millennials starting coming along in 1982, Xers wound up with an 18-year generational period rather than the usual 20 years.

Of course, it’s not as if marketers give a consolation prize. The fact is, Gen X is statistically small, and as Taylor puts it, “numbers matter, size matters, and that’s one thing that Gen X has going against it as the target of marketers.”

Gen Xers grew up before the Internet, then learned to adapt to digital technology in their early adulthood. Their age leaves them with one foot in the past and one in the future—and that leaves marketers confused about which platforms should be used to reach them.

“Brands feel like they can make more black-and-white assumptions about boomers and millennials,” says Erin Winters, vp, marketing strategy at Acxiom. Millennials, she notes, “spend most of their lives on digital media. Boomers spend the lion’s share of their lives in the offline world. Gen X is right there in the middle.”

In fact, a marketer trying to strategize how to best target an Xer is faced with a complicated decision. According to Forrester Research, traditional media is still important to Gen X (48 percent listen to the radio, 62 percent still read newspapers and 85 percent have favorite TV shows). But at the same time, Gen X is plenty savvy when it comes to digital media. A survey by Millward Brown Digital found that 60 percent of Xers use a smartphone daily and 75 percent are routinely on social networks. Gen Xers are quite active online as well when it comes to banking, shopping and researching products they want to buy.

That leaves brands having to figure out just the right mix of old and new media.

Want confirmation that reaching Xers is a challenge? Just try Googling “How do you market to Generation X?” The results are all over the map. “Try word of mouth,” suggests one blog. “Think social,” another advises, while yet another proposes “an omnichannel approach.” Based on the data above, one might surmise that the best option would be D) All of the above.

Just for the record, Billy Idol’s first band took the name Generation X in 1976. But those Americans born after the baby boomer generation didn’t assume the moniker until after Douglas Coupland’s best-selling 1991 book Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture. In 1993, Neil Howe and William Strauss published 13th Gen, the name they gave post-boomers. Why does any of that matter? “When we wrote our book, Generation X still didn’t have a name,” Howe explains. “Over 30 years after their birthday, they didn’t have a name. I think that’s germane.”

To Howe’s thinking, the culture’s failure to give something so basic as a name to the post-boomer generation had a way of telegraphing its inferiority. “Nobody paid attention to them,” he says. “And they internalized that.”

Never mind that the term Generation X, once it did take hold, was loaded with negatives. Like Madame X or Malcolm X, it implied something anonymous or scandalous. “C’mon, Generation X? What is it hiding?” Howe says. “We named them X because we didn’t want to name them anything worse.”

But in fact, we had. Consider that all the other labels applied to Xers are also negative: baby busters, latch-key kids, slackers, the “Why Me?” Generation, the New Lost Generation. Howe believes that Xers felt the scorn of all these. “It was epitomized in Wayne’s World: ‘We are not worthy!'” he says.

Is it any wonder, then, that many marketers also see Gen X as not worthy?

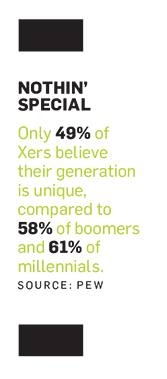

As a recent Pew Research study put it, “Generations, like people, have personalities.” And there’s no question that boomers and millennials each see themselves as a distinctive group. Boomers were defined by the civil rights and women’s movements, and by challenging authority. Millennials, who ushered in social media and gay marriage, see themselves as confident, tech-savvy and socially progressive.

What do Xers think makes them special? Well, that’s the problem.

A prior study by Pew, this one from 2010, found that only half of Xers saw their generation as unique, while there was little agreement among those who thought it was unique about why. One might conclude that if Xers don’t find anything particularly distinguishing about their group, why would marketers?

The problem, once again, seems to be their in-between status. Taylor points out that his generation, the baby boomers, “made a lot of noise. People said we were boomers.” Millennials made a lot of noise, too, and certainly know that they’re millennials. “With these bookend generations, you see the start of a difference that makes for a big story,” Taylor says. By contrast “Xers represent a transitional generation, and that’s less compelling.”

There’s another theory. Generational change expert Neil Howe, founder of LifeCourse Associates, suggests that the overwhelmingly negative stereotypes about Generation X may have caused many Xers to disassociate themselves from their own age group. Howe recalls interviewing Xers in the ’90s. “I’d ask them, ‘What do you think of your generation?’ And they said, ‘I don’t belong to that generation.’ That’s how negative the stereotype was,” he recalls.

Generation X “doesn’t like to think of itself as a generation,” he says, “and that may be as important as anything in diminishing the tendency to talk about them.”

While many marketers have given Gen X short shrift, that is not to say every brand ignored them. Wendy’s, Chipotle and Red Lobster are just a few that have long viewed Gen X as core customers. The same can be said for Cheerios, Virgin, Honda and Patagonia. And Apple‘s “Think Different” is a Gen X mantra if there ever was one.

“My feeling is that we’ve been targeted our entire lives,” says author and marketing authority Seth Godin (who regards himself as “pioneer Gen X”). “But there’s a thing that might make it seem otherwise: American pop culture got mostly baked from Kennedy through Nixon, which means that the soundtrack and the imagery that has been used on us is still Beatles/Mad Men/CSNY/Godfather. In other words, baby boomers made our world.”

And though the stereotypes about Gen X might be understandable, even defensible, they can also be misleading. Because if Xers weren’t an attractive target in their teens, they certainly are now. “Others have been concerned that Gen X isn’t going to give you the ROI, but we’re not afraid to target them,” says Tom Peyton, avp, advertising at Honda. “Gen X is not quite as big and sexy [as millennials], but at the end of the day, they are prime time in their income and they can buy a lot of expensive new cars.”

He’s right about that. Research from American Express revealed that Xers have more spending power than any other generation. And while Gen Xers are only a quarter of the population or so, Acxiom’s Winters notes that they account for 31 percent of consumer spending. “You’re talking about parents with children,” she says. “The buying power is massive.”

Gen X also has a home ownership rate of 82 percent, according to research from MetLife. And despite their purportedly cynical attitude, Xers happen to boast the highest rate of brand loyalty, at 70 percent, according to eMarketer.

Those stats don’t surprise FCB’s Deb Freeman—not only because she is an Xer herself, but because, following the Lincoln Financial campaign, she is working on two other Gen X-targeted spots for major brands.

Noting the enormous spending power of Xers, Freeman says, “You could call this the sandwich generation, but there’s a lot of meat in that sandwich.”

This story first appeared in the April 4 issue of Adweek magazine. Click here to subscribe.