What do you do with broken products? You fix them.

![[Photo: courtesy Fairphone]](https://assets.fastcompany.com/image/upload/w_707)

Chances are, you toss it and buy another one. It’s only a toaster, after all. But what if your toaster was designed so that it’s easy to fix? What if a screwdriver and a replacement part could save you that $30 and the device from the landfill?

A toaster might seem insignificant, but your inability to fix it and the subsequent impulse to ditch it is part of a broader problem in how products are designed, manufactured, and consumed. Because it’s not just one toaster–it’s the vast number of appliances, electronics, furniture, and even clothing that end up in the landfill when they break. In terms of e-waste alone, the world is generating more than 55 million tons of it every year.

Products typically aren’t designed to be fixed. But now, a movement is under way, pushing back against this culture of disposability. Whether their focus is on repair as a mechanism for sustainable living, as a power struggle with corporate interests, or just as the best way to deal with a broken object, these groups have a message for designers: Don’t just design with the end user in mind, but with the end of the product’s life in mind, too.

“Even with the phrase user-centered design, we’re oriented around the consumer,” says Daniela K. Rosner, an assistant professor of design and engineering at the University of Washington. “It’s very disheartening to think that the product at the end of the day is just about the moment in which it’s sold to a consumer rather than the life of that thing beyond.”

THE DECLINE OF REPAIR

Product design’s shift away from repairability has been a gradual one that has come to a head in the past 10 years. The cost of producing electronics has plummeted, so more and more of them are made cheaply by companies that save even more money by not maintaining an inventory of parts–something that would have been unheard of in previous decades. That’s according to George Girod, who started a casual group meetup called a “repair cafe” in Marquette, Michigan, and put himself through college by repairing televisions in the late ’60s and early ’70s. “When I was fixing TVs, I’d have to special order some parts, but manufacturers would have them [in stock]for seven to eight years,” he says. “They couldn’t sell it if they couldn’t help you keep it running. People wouldn’t stand for it.”

But that’s not the case now. At one repair cafe earlier this year, someone brought Girod and his group a flat-screen TV with a defective main board. “God help you if you want to take it apart,” he says. “That was our toughest. It was not designed to be repaired at all.”

Then there is what Vincent Lai, the leader of the New York City-based group the Fixers Collective, calls “design anorexia.” As manufacturing has gotten cheaper, electronics have gotten thinner and lighter. “Fifty years ago when people wanted to buy a land-line phone, weight was still a criteria in terms of whether you bought something or not,” Lai says. “But 50 years ago, people chose a heavier item. Things have become lighter and lighter to the point that their original functionality can be compromised.”And not just lighter–thinner, too. Lai is referring to the problems both Samsung and Apple have had with some of their smartphones. Apple’s iPhone 6 Plus would bend just by being in people’s pockets, a fiasco known as “Bendgate”; worse, Samsung’s Galaxy Note 7 would spontaneously combust despite critics initially praising the phone’s “premium design.”After recalls and investigations, the company finally determined that this was because the phone’s battery casings were too thin. This quest to be the thinnest, lightest device on the market has implications for repair: To save space, designers and engineers now solder and glue together parts that once would have been screwed into place because it’s the easiest way to assemble an incredibly compact electronic device.

This shift has made repairing devices incredibly difficult while serving to concentrate power in the hands of the company that makes them. Lai says that once upon a time, the best way to extend the life of your laptop was to upgrade the memory, which you could do for about $100. But with new laptops, he says, you need to change the logic board or motherboard entirely because everything is soldered together–that’ll cost you at least $1,000.

iPads are some of the worst offenders. Set designer Sandra Goldmark, the cofounder of New York City’s mobile shop Pop Up Repair, says that in her first repair session, she and her colleagues took in several iPads, including one with a smashed screen. They bought a new screen to install, and then their troubles began. “It’s impossible,” she says. “It’s not designed to come off easily. Then you have to glue the whole thing back on.”

“Even Apple Geniuses don’t fix iPads,” says Kyle Wiens, the founder of iFixit, an online repair manual platform. “They mail them back to the central depot. The reason for that is the product design.”

There are serious incentives for companies to produce products that can’t be easily repaired. That means that customers are forced to rely on the companies themselves for any maintenance rather than (often cheaper) independent repair shops. For instance, Apple charges $79 plus shipping to replace an iPhone battery, whereas iFixit sells the battery plus a DIY battery-changing kit for $19.95–though it’ll take 15 to 45 minutes of your time coupled with some paranoia about breaking your phone. “They do their best to make it impossible to repair,” Girod says. “Plus that allows them to have a rapid cycle of obsolescence. By the time you’ve paid off your Samsung 6, they’ve got a much better Samsung 7 you just have to get.”

That’s not to mention cheap home goods. Your toaster that broke? “That’s ultrasonically sealed together. When it fails, there’s no way to get in and swap it out,” Wiens says. “When it takes an hour to fix a toaster and it’s $30, maybe just get another. But it’s another crappy toaster. If you bought a better toaster, and could get it fixed, it could last 30 to 50 years instead of 3.”

THE CASE FOR REPAIR

Repair has indisputably been declining as an industry and as a practice, and that’s frequently due to the way that products are designed. So it stands to consider why building repairability into a product matters in the first place.

As landfills fill up, conversations in the design world have turned to how to sustainably design products. But that often focuses on using biodegradable materials. While that conversation is important, repair as a part of the design process is another way to significantly mitigate the waste that designers’ work ultimately ends up producing. If you fix something, that means you save that object from the landfill, but it also means you don’t need a new one. Sandra Goldmark of Pop Up Repair believes this is the real benefit, that for every pound of waste diverted from landfill, you can reduce as much as 40 times that amount by not manufacturing new stuff upstream.

But she envisions a culture that goes even further than that–and there’s a business case to back it up. “If we really began to repair as a society, if manufacturers and retailers say they could make money from fixing that toaster, they could have designers design things for repair, for upgrade,” she says. “There’s all kinds of ways from making something easy to open, to how can we imagine a whole series of life-cycle steps for this product that people will be excited about. You can begin thinking about design as a way to plan for this. Repairing doesn’t have to be an afterthought.”

With corporate interests letting repair fall to the side, a global movement dedicated to keeping repair alive has exploded in the past five years, mostly through organizations and businesses without a traditional storefront. For instance, Repair Cafes are occasional meetups where community members bring their broken stuff and fixers do their best to help, often for free or for a small donation. There are more than 1,300 chapters around the world. Kyle Wiens’s organization iFixit runs Fixit Clinics in California under the same principle.Groups like Vincent Lai’s Fixers Collective work on a similar model, asking for a $5 donation plus the cost of parts to fix electronics, furniture, even clothing. One night this spring, I visited Lai in the upstairs of Brooklyn Commons, a cafe where the group typically meets once a month. We sat around a table in a dusty room, the table covered in tools. One woman had brought a broken lamp. Another man had a clunky laptop the memory of which he wanted to update. Once their items had been fixed, I asked Lai to open up my laptop. While watching him fix other peoples’ electronics, I realized that I’d never seen the inside of the device that I spend hours on every day. Unlike Apple’s Genius Bar, where cheerful employees listen to your woes and then take your electronics away to be examined far from your prying eyes, repair groups often want you to get involved in your own repair. But my heart pounded as I watched Lai slowly undo the tiny screws that secure the back of my laptop. I’d never realized before how deep my reverence for technology and fear of breaking it was. It’s exactly this kind of detachment, this gap between people and their devices that the repair movement is trying to fix.

CAPITALIZING ON REPAIR

Companies are also hopping on the repair movement bandwagon. Pop Up Repair and iFixit frequently partner with Patagonia, which has a robust repair program called Worn Wear, where customers can shop for clothing that’s been repaired and trade in their own clothes: “One of the most responsible things we can do as a company is to make high-quality stuff that lasts for years and can be repaired, so you don’t have to buy more of it,” the website reads. The company has detailed guides to repairing and taking care of different types of fabrics on iFixit’s website.

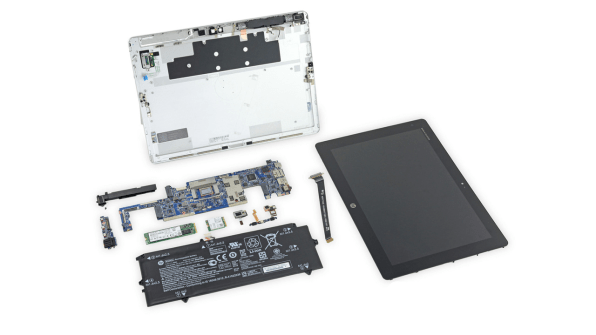

In the electronics space, Wiens praises PC makers like HP and Dell for their dedication to repairability. On the iFixit website, where Wiens reverse engineers electronics in “teardowns,” he praises HP’s Z1 tablet with a 10 out of 10 for repairability because of its modular design, use of screws and plastic fasteners instead of glue, and a diagram of how it’s put together inside the machine. Beyond the design, HP provides PDFs and videos to help with repairs. Dell’s XPS tablet gets a 9 out of 10, for similar reasons, with the added benefit of having labeled wires and color-coded, standardized screws.

There’s a business argument for designing products that can be easily repaired and then providing the means to maintain them. “[HP and Dell] see providing service as part of the value of providing the product,” Wiens says. “It maintains the resale value of their products, making people willing to spend more on a brand product up front. That’s a differentiator. In Africa, people would much rather spend more money on a used Dell than a brand-new Chinese clone computer.”

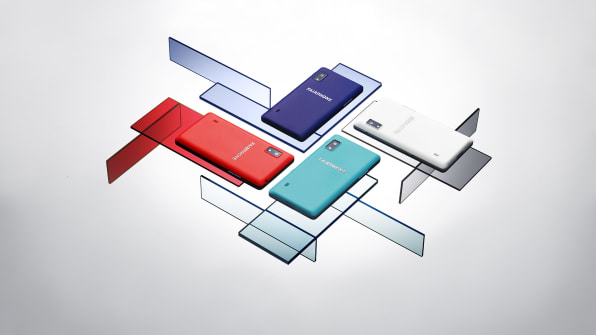

Startups are also trying to take advantage of the repair movement. Take Fairphone, which launched its most recent model in 2015 with the mission of creating an ethically made, modular phone that would actually last. A key part of that is a design that makes repair as simple as popping out the malfunctioning part and replacing it with a new one. “If something happens to it, the usual elements that tend to break, the display, or the electromechanical interfaces, the buttons, we can change everything using just a screwdriver and a couple of minutes,” says Olivier Hebert, Fairphone’s CTO.The phone was designed so that the primary expensive electronics, which don’t evolve as rapidly as the phone’s other components, are grouped together in a single module. Then the rest of the parts–the USB drive, the microphone, the speaker, the camera–are all divided into submodules. If one breaks, you take out the module it’s a part of, unscrew it, and change out the part. The company sells spare parts for its phone on its website, so getting ahold of one is never an issue.

The phone’s sustainability ambitions are built on the idea that the most wasteful thing you can do is buy a new phone. “The most sustainable phone you can use is the one you’re already using,” Hebert says. “If we make it easy for you to keep using the same phone, we reduce the environmental impact of making a new one. Most of the energy consumption and material depletion happens in production.”

The startup is betting on the fact that an endless cycle of incremental upgrades isn’t a good business model in the long run. “At some point the system will break,” he says. “If it’s easier to repair in general, it’s also easier to produce and maintain. It’s easier for just about everybody.”

Remade is another startup trying to build a sustainable business model on repair. The company, which started in 2011, has a part repair shop, part makerspace, part thrift store, part learning centered called the Edinburgh Remakery, and just announced plans to franchise. But besides Remade and Fairphone, there are few startups trying to address the e-waste problem that many of their peers are adding to. And it’s hard to say if Fairphone has been successful–Hebert says that the company’s average customer is a mid-30s German man with at least a master’s degree and above average disposable income. That’s a pretty small segment of the population. I’ve certainly never ever met anyone who has a Fairphone.But even if Fairphone flops, there are signs that the movement is trickling down into student design work. Take student Kasey Hou, who just graduated from the University of Edinburgh with a degree in product design. For her thesis project, she built a repairable, flat-pack toaster.

To learn how to build a toaster from scratch, Hou decided to take apart some existing models. Problem was, she had to physically break them open in order to take a look inside. “They’re not designed to be repaired,” she says. “People can only throw things away when they don’t work.”

But her flat-pack prototype, which takes less than an hour to build, was designed to help people to understand how the appliance is put together so they feel empowered to fix it when it breaks.

“We always say that design is to solve problems, but we often ignore the fact that it also creates problems,” she says. “So I think designers should be responsible for things they design.”

–

This article first appeared in www.fastcodesign.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +9714 3867728 or mail: info@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com