A recent video ad for Arby’s showed pro golfer Andrew “Beef” Johnson on the green and pitching the ball into an Arby’s cup. The ad itself was fairly ordinary except for this: If you saw it on an Android phone, you could not only watch and hear Johnson but feel his footsteps as well.

This type of so-called haptic technology, which transmits vibrations, has been used in gaming for decades. Now marketers, including Stolichnaya Vodka, BMW, Royal Caribbean, and Truvia, are starting to apply haptics to their ads as well.

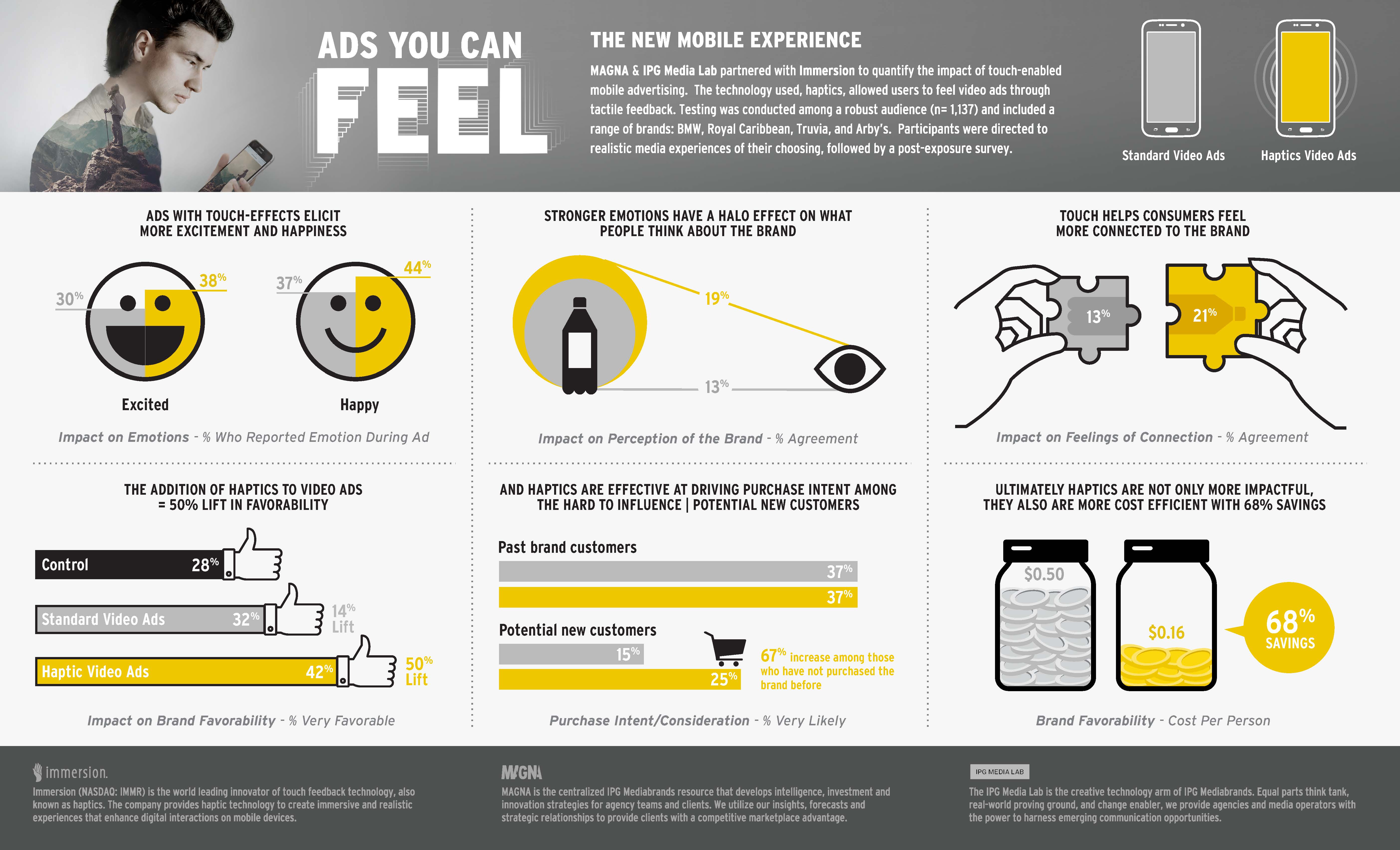

So far the results are encouraging. Adding haptics boosted the happiness and excitement levels consumers felt by 7% and 8%, respectively. The ads also raised brand perception by 6%, according to a study by IPG Media Lab, Magna, and Immersion. Others have claimed success with haptics, too. Mobile phone maker Hauwei said its ads using haptic technology were 10 times more effective than its standard ads.

Of course, the novelty factor might be at play. But as IoT devices begin to become more of a standard feature of the landscape, more marketers could start tapping haptics to boost their campaigns.

A Haptic History

Haptic is to touch as optics are to sight. Broadly speaking, braille is considered a haptic technology. Its use in computing goes back to 1976, when the Sega video game Moto-Cross featured haptic feedback that simulated the feel of a motorcycle. The feature was a success, and other video-game makers later included haptics in their games as well.

Such games used a component called an actuator, which vibrates to appeal to our sense of touch. Later, most cell phones (not to mention pagers) used the feature as an alternative to audible notifications.

With the introduction of touchscreens, phones started to offer more of a palette of experiences. By 2010, Samsung, LG, Nokia, and Research in Motion (now BlackBerry) were offering haptic feedback. At the time, the range of haptic feedback was pretty limited, but the technology has been progressing. In particular, the Apple Watch simulates the feeling of a rubber band snapping back when a user exits the limit of a field. The iPhone 7 also offers a range of sensations. Changing the date or time on an iPhone 7, for instance, mimics the feel of a mechanical wheel. A game called Alto’s Adventure simulates the feeling of sliding on ice. A handful of other iOS games also feature haptic effects. Google Play also has a section of “Games You Can Feel” for Android.

With the introduction of touchscreens, phones started to offer more of a palette of experiences. By 2010, Samsung, LG, Nokia, and Research in Motion (now BlackBerry) were offering haptic feedback. At the time, the range of haptic feedback was pretty limited, but the technology has been progressing. In particular, the Apple Watch simulates the feeling of a rubber band snapping back when a user exits the limit of a field. The iPhone 7 also offers a range of sensations. Changing the date or time on an iPhone 7, for instance, mimics the feel of a mechanical wheel. A game called Alto’s Adventure simulates the feeling of sliding on ice. A handful of other iOS games also feature haptic effects. Google Play also has a section of “Games You Can Feel” for Android.

In addition, the trackpad on the MacBook Pro re-creates the experience of touching a button when there actually is none. Similarly, the trackpad could mimic other textures as well, including holes, bumps, and indentations.

Haptic Ads

It was just a matter of time before someone decided to apply haptics to ads. For example, Immersion, a 24-year-old firm that has applied haptics to medical equipment and gaming, has been experimenting with advertising since 2015.

Chris Ullrich, VP of user experience and analytics at Immersion, said the first ad using haptic technology was a teaser for Showtime’s Homeland’s Season 4 series premiere in 2015. That ad featured a haptic simulation of a bomb explosion. The click-through rate for that ad was five times the industry average. Another ad that year Immersion worked on for Stolichnaya Vodka let consumers simulate the feel of a cocktail being made in their hands.

So far, Immersion doesn’t have much competition. Though competing firms Hap2u and Ultrahaptics also create haptic experiences, neither has so far offered them for advertising. In its 10K filing from last year, Immersion warned that partners and customers could develop “their own haptic solutions.”

(At this writing, Immersion’s TouchSense ads were available only for Android phones because the company is in the midst of litigation with Apple. Ullrich said there’s no technical barrier to running haptic ads on Apple devices.)

More recently, a study by IPG and Magna found that Immersion’s TouchSense ads performed better than standard video ads. In particular, there was a 62% increase in feelings of connection to brands. Some 38% of respondents said they felt excited after viewing an ad with haptics versus 30% for those who saw an ad without haptics. Haptic ads also made viewers 7% happier.

Of course, the novelty factor could be influencing those results. Banner ads were once novel, but now no one clicks them. “Whenever you have something different, it gets people’s attention and those companies tend to get a good response,” said Laura Ries, president of branding consultancy Ries & Ries.

“It’s possible there may be some of that,” Ullrich said. Ullrich pointed to a parallel in gaming. “When Rumble [a game featuring haptic technology]came out in 1998, you could argue the same thing–do games really need this? And what we have seen is that it has been adopted in numerous game experiences because it does add meaningful value.”

That said, Ullrich warned advertisers not to overdo it. “You can run the risk of a backlash,” he said. “Our research has indicated that there’s a preferred level of density for haptic effects where it’s a meaningful impact but isn’t annoying or causing user frustration.” Unlike audio or visual effects, haptics need to be “discreet,” he added.

Shepherd Laughlin, director of trend forecasting for J. Walter Thompson Worldwide, said haptics are potentially a “powerful tool for digital storytelling,” but “so few people have tried these devices that it’s too early to say if this will work in advertising or have any staying power.”

Beyond Phones

As virtual reality, touchscreens, and wearable technology, such as Google’s Project Jacquard with Levi’s, become more common, brands will have more opportunities to use haptics. For instance, realtor Halstead Properties is using haptics as part of a VR experience. Consumers who try it can feel what it’s like to turn a door knob or touch closets and faucets at a home they’re checking out.

In this new environment, a brand could also create a haptic identity that’s the tactile equivalent of the Nike swoosh or Intel’s jingle. Imagine, for instance, if a brand was known for a touch sensation that evoked putting your finger in sand or one that simulated the ripples in a pool of water. “Why not?” Ries said. “Brands have owned certain hues of colors and sounds. There’s no reason why a certain vibration couldn’t be connected to a brand.”

Hayes Roth, principal with HA Roth Consulting, agreed. “Over time, a few brands will figure out how to use it without being creepy,” he said. “It could add a new dimension to the brand experience.”

Marketers are already using haptics to differentiate their designs. Toyota has demonstrated an in-car touchscreen that responds to the driver’s touch with a slight haptic bump. A system from Bosch also simulates the feel of pressing buttons and activating clicks. Some Cadillacs’ seats also rumble to notify drivers of an impending collision.

At the moment, Immersion has no plans for bringing haptic marketing to IoT. “The applications are interesting,” Ullrich said. “But we’re really focused on the short term on working with our partners [on IoT devices.]”

While touch may never be on equal footing with visual or optic brand elements, it might be another alternative, along with scent, that can help brands differentiate themselves in a post-mobile world where consumer attention spans grow ever-shorter. As Ries noted, it takes the brand some time to read a logo, but “for stimuli like visual, smell, and touch, it goes directly to the brain. Without even thinking about it, you get a reaction.”

–

This article first appeared in www.cmo.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +9714 3867728 or mail: info@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com