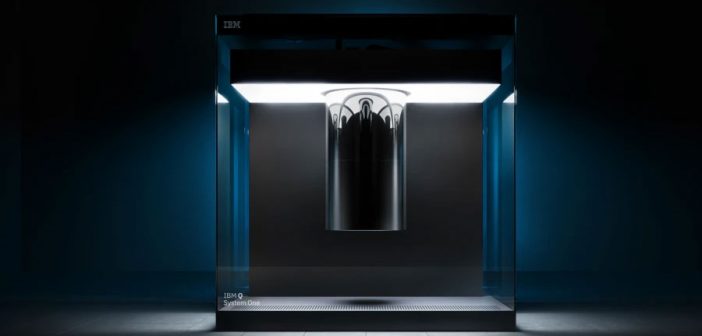

With help from Map Project Office and Universal Design Studio, IBM’s Q System One is designed for the future of computing. And it’s mighty pretty.

The computer you’re reading this on right now uses binary code, a series of ones and zeros that work together to translate human commands into a language the computer can understand. Now, an entirely different way to think about computing that’s been around for decades is on the cusp of being realized. Instead of ones and zeros, this type of computer uses a new language where each quantum bit–called a qubit–can become both one and zero at once. That means it could solve vastly complex math problems that modern computers struggle with, like those that underlie the security of the internet.

Quantum computing is still at an experimental stage, but at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, IBM revealed what it is calling the most advanced system so far, the Q System One. To help the public understand what the computer does, IBM turned to industrial design firm Map Project Office–known for designing DIY computer kits, clever utensils, and Virgin’s in-flight experience–and interior and architecture firm Universal Design Studio, which has designed the Ace Hotel London and retail spaces for H&M and Rimowa. Together, they worked to give the computer a polished, consumer-facing form that would also work within a modern data center.

The exercise was partially about marketing–something of an IBM speciality–but there were also some serious technical challenges to overcome so that the computer could one day be scaled. Previously, the Q System One was just a scattered group of equipment stationed in IBM’s office in Yorktown, New York, but Map and Universal endeavored to give it a single cohesive form so it could easily slide into modern data centers.

This is no ordinary computer: Qubits are incredibly sensitive to the outside environment, and fluctuations in temperature, vibrations, and electromagnetic waves can throw off their delicate balance. For this reason, IBM’s quantum chip, which includes 20 of these qubits, needs to be suspended inside a refrigerator called a cryostat that can create a super-cold environment similar to outer space.

AN AIRTIGHT GLASS CUBE

To ensure these conditions were met, Map and Universal created an airtight, nine-foot-tall glass cube, where a stainless steel cryostat cylinder is suspended from a cantilever in the center of the space. The back of the cube is a careful arrangement of the rest of the analog piping and wiring necessary to make the entire system work together, none of which could come into contact with each other, lest their vibrations disturb the qubits. “There’s a lot of space required between things,” says Jason Holley, Universal Design Studio’s director who co-led the project. “It goes against everything we know about digital technology, which is getting smaller and smaller.”

The cube is able to maintain a stable environment, regardless of where it’s placed–a necessary detail, as IBM begins to commercialize the quantum system. Because the cube is a single unit rather than the kit of parts that previously made up IBM’s quantum computer, it’s easier to slot it right into modern data centers. The computer inside will ultimately be accessed from the cloud (anyone can already run experiments on IBM’s current prototype, right from a computer at home).

But the design isn’t all function over form. To make the cryostat–which was originally suspended from a four-post frame in IBM’s lab–more visually striking, the designers wanted to suspend it from cantilever. That way, it would look like it’s floating in midair in a glass vitrine. The team worked with glass manufacturer Goppion, which has created glass cases for the Louvre’s Mona Lisa and the U.K. Crown Jewels at the Tower of London–a fitting partnership given that the design deliberately puts the technology on display.

Originally, though, the engineers worried that the cantilever would destabilize the carefully calibrated conditions necessary to make the computer work. After working through a series of prototypes, the design team created a cantilever that was more stable than the previous four-post frame.

The cantilever also gives engineers 360-degree access to the cryostat for maintenance and upgrades. The engineers are now able to perform updates more than 10 times faster because all the components are together in a single object that’s three times smaller than the original lab setup. “It’s not just this beautiful glass vitrine and this artistic steel thing hanging from the top,” says Will Howe, director of Map Project Office who also led the project. “A lot of thought [went]into how it works in a data center environment and how people use it and maintain it on an everyday basis.”

The simple geometry of the cube also reflects some of the underlying ideas about how quantum works. “[Quantum computing] starts to evoke properties that happen at molecular level. This is how nature organizes things and thinks about things,” says Holley. “We tried to evoke that in the simplicity of the design here. It’s almost as stripped back and a purely geometric as we could make it.”

What’s more, the design is supposed to give future customers, like businesses or universities, a mental image of what a quantum computer looks like. After all, the quantum computers of tomorrow likely won’t ever leave data centers–or even IBM’s offices. “[IBM has] gotten to a point where they want to commercialize the technology: to do that you need to capture the public’s imagination,” Howe says. “If you want to sell it, people need to see what they’re buying.”

–

This article first appeared in www.fastcompany.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +9714 3867728 or mail: info@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com