The Supreme Court sided with Samsung in its ongoing legal clash with Apple. Design patents may never be the same.

[Photos: Apple, Samsung, United States Patent Office]

In a landmark decision, the court ruled that granular design patents could be treated as just that, granular, rather than the all-encompassing, powerful patents that the law currently describes them as. “Oh, this is good,” said Sarah Burstein, associate professor at Oklahoma College of Law, as she read the ruling over the phone with me. “This is exactly what I hoped they would do.”

Now, the case will go back to the Federal Circuit for the specifics to be sorted out. Samsung may or may not recoup hundreds of millions of dollars as a result, but the decision will impact all companies filing design patents for years to come. Here’s a breakdown of what happened and why it matters.

[Photo: via SCOTUSblog]

WHAT WAS AT STAKE?

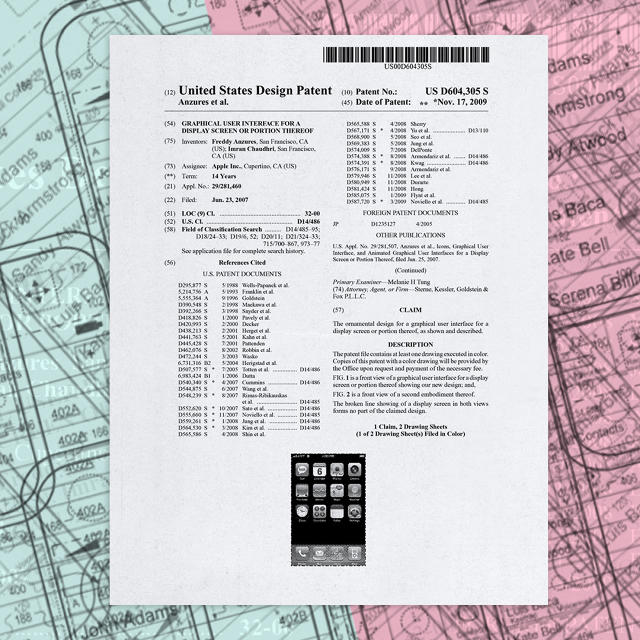

In December of 2015, Samsung was forced to pay Apple its complete profits from 19 Samsung products that were found to infringe on Apple patents by the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit—a staggering $548 million. But Samsung was hoping to get $399 million of that money back. You see, Samsung wasn’t found guilty of copying the iPhone as a singular invention. Rather, it was found guilty of infringing upon three specific design patents: The rounded corners on the front of the iPhone, the rounded corners plus a rounded bezel of the iPhone, and a grid of app icons you see in iOS.

Those might seem like small details, but because of a century of strange legal precedent, ripping off even the smallest design patents can cost the infringer the complete profits of their product, or what the law describes as the “article of manufacture.” As such, Samsung owed its entire profits from each infringing product, resulting in the massive payment it made to Apple last year.

By appealing to SCOTUS, Samsung was hoping to prove that those granular patents weren’t worth all $548 million—and in doing so, challenged legal precedent about the power of design patents.

WHAT HAPPENED AT THE SUPREME COURT

The Supreme Court has ruled that the “article of manufacture” addressed within a design patent doesn’t need to be a complete product, contradicting Apple’s argument and the history of design patent law. Instead, the article of manufacture can be just part of a product. And as a result, if someone infringes upon a design patent, the patent holder would be entitled to just partof the profits, too.

Notably, the Supreme Court did not decide exactly how this new precedent will work, and its decision is bound to create a new era of debate around design patents. Who will determine if Apple’s rounded icon style is worth 1% of the Samsung Galaxy profits, or 10%, or 99%? How will these arguments be presented? What evidence will the companies need to provide? All of these issues will need to be carefully considered when coming up with a legal “test” that judges can use to determine how much of an infringing company’s profits the original patent holder deserves.

Instead of developing this test on their own, SCOTUS is kicking the case back down to the Federal Circuit, which is in charge of dictating how design patents play out in court. “The Supreme Court is saying to the Federal Circuit, ‘your test is wrong, but we’re not picking a new test,’” says Burstein. “They’re sending it back to the Federal Circuit to come up with a new test.” It could be many months or even a year before we know what the Federal Circuit decides.

WHAT DOES IT MEAN FOR DESIGNERS?

By the end of the trial, as the companies made their final case to the Supreme Court, even Apple had ceded some ground on the all-encompassing power of design patents. But no one—not Samsung, not Apple, not even the argument presented by the federal government—offered a full solution at the trial.

“To be really frank with you, this is the best way they could have resolved the case,” says Burstein. “Given the strange path to the Supreme Court, I was really worried they were going to pick a test . . . that they didn’t have time to think about.” Burstein points to 40 years that the Supreme Court has spent ironing out the strange legal issues around cheerleader uniform design. “I don’t think we need 40 years here, but we need more than two minutes,” she says.

Now, the Federal Circuit will have time to devise a new approach to proving and parsing the value of individual design patents, and the precedent that follows in the next chapter of Samsung v Apple will determine exactly how design patents are treated in court for many years to come.

“It’s possible they’ll design a rule that makes design patents less valuable . . . for right now I don’t think it’s possible to say one way or the other,” says Burstein. “I’m sure there will be lots of hand wringing about how design patent is [destroyed], but I don’t think it’s true. In 99% of cases, I think [companies]will still get these things, and they’ll still be scary.”

This article first appeared in www.fastcodesign.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +9714 3867728 or mail: info@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com