Kevin Systrom On Instagram’s Big Moves: “It’s Almost Riskier Not To Disrupt Yourself”

Kevin Systrom, cofounder and CEO of Instagram. PHOTO: DAVID PAUL MORRIS/GETTY IMAGES/BLOOMBERG/CONTRIBUTOR

More than six years after its debut, Instagram remains the archetypal example of an app that was a phenomenon the moment it hit the App Store. The proposition it offered–simple, elegant photo sharing, with fun creative tools–kept on accumulating new fans at such a clip that you can understand why the company was hesitant to mess with its formula, even after it became part of Facebook in 2012.

Recently, however, Instagram has done a whole lot of evolving, and it’s done it in rapid-fire fashion. Most notably, the company integrated something nearly identical to the concept of Snapchat’s “Stories” mini-multimedia shows into its own app, and then built it out with features such as live video streaming. The idea was so immediately popular inside Instagram that it changed the app in a way that’s rare for any one feature to do.

For the April issue of Fast Company, I talked to Instagram cofounder and CEO Kevin Systrom about topics such as how the company came to have a broader view of its purpose; why it added Stories and what it’s doing to make sure they feel like they belong in the app; and what it’s like to run an enormous social network that’s owned by an even larger one. Our conversation took place on January 24, 2017, at Instagram’s new headquarters in Menlo Park, California, and has been edited for publication.

MISSION IN TRANSITION

Given how much Instagram has changed recently, maybe we should start by talking about exactly what you are nowadays.

Okay, so “What is Instagram?” is the question. The best way to answer that is through the mission. Strengthening relationships through shared experiences, that’s what we do.

That wasn’t always clear to everyone. It wasn’t always clear to us. It wasn’t always clear to Facebook. And it wasn’t always clear to the world. But when a company starts, it’s usually a very focused point of effort on a specific feature. In our case, it was photo sharing. And that was . . . October 6, 2010. The date gets farther away as I get older.

When we started, it was all about sharing beautiful photos. And that’s not actually why people downloaded and used Instagram. Why they downloaded and used Instagram was because they were sharing a part of their life with people who cared. We just happened to use visual media to bring people closer together. So when I could share a trip I was on, when I could share what I was doing in the moment, taking my dog for a walk, being with my family, connecting with my family when they’re on the East Coast and I’m on the West Coast, that was all about strengthening our relationships.

But for a while, we kind of just focused on photo sharing. We added added new filters, people cheered. We added hashtags—there was a day when hashtags didn’t exist on Instagram—people cheered, because now they could categorize their photos.

And all of those features are fine. But as you start to grow, you realize that you need to do more than what you were doing in the past, because people’s needs evolve as well. The advent of faster phones with better connections and better cameras meant that people could strengthen their relationships through many different kinds of shared experiences, one of which was video.

A shared experience of taking a video and then sending it to someone else meant that you could grow very close with them, whether it was someone getting married, an important moment in life like your kid’s first steps, or something as beautiful as some clouds rolling over a big mountain that you see. That was a format change, and people looked at us at the time and were like, “Why are you putting video inside of Instagram? That makes no sense.”

I’m not sure we actually got it right, either. Because we applied some of the same assumptions to video that we had to photos: “Oh, you add filters to it and everything just works.” But it turns out that video is much less about the artistic quality—although there are many beautiful videos on Instagram—and it’s much more about the message that it contains. Likes, for instance, are far less relevant for videos, whereas views are far more relevant.

I’d say only a couple of years ago did we start to realize some of these nuances with the format. That views were more important, likes were less important to people. That the content was different, that duration was different. And we started investing in changes to our formats.

A big change happened when we decided to go non-square. For a long time, it was like Okay, we’re going to only have square video and only have square photos. And that’s because it’s artistic, it’s easy to frame up something. And it comes across as different.

But it turns out that we might have been too precious about trying to keep a square format. Because the second we changed and we allowed for non-square, suddenly people started producing different types of content. And they started producing more, actually. We had an A/B test at the time of square and non-square. If you allowed people to post their photo in landscape or portrait, they actually feel more free to share.

Not at that moment, but a confluence of events around that moment, made us realize that we’re not a photo-sharing company. We’re all about a shared experience through the different formats. As we launched things like Instagram Direct, with sharing of photos privately, Stories, Live, someone on the outside who doesn’t know all of this context could be like, “Why are they just adding a bunch of features?” If we just added a bunch of features, then I don’t think it would have worked, if it didn’t hang together underneath some unifying concept.

But actually, the unifying concept was that we wanted to bring people closer to each other through these types of shared experiences. And if we had a product that had different types for different use cases, and brought you together closer to those people that you follow and follow you, it would actually work.

And proof of this is launching Instagram Stories, a new format that was a big bet. It’s different. It’s not based on likes. It’s not based on artistic quality. In fact, it encourages the opposite of what Instagram stood for in the first place. But people took to it. And in the first couple of months, we had over 100 million people using it.

Was that shocking to you, or did you think it had the potential to catch on that quickly?

It’s hard to ask the CEO, because the CEO always believes things are going to work. Otherwise we wouldn’t be working on them. But we, and I, had a conviction that it was the right thing to do.

There’s one argument that says we’re adding to and changing our product in disruptive ways. There’s another way of looking at this, which is we’re adding features that should have been there the entire time.

Remember when we introduced video? Vine had just come out and was a big thing. I think the conversation was like, “Instagram should just have this feature.” And another company realized that and produced a product that effectively was Instagram for video. They innovated a bunch and had a bunch of different stuff. But effectively at the root of it, it looked like Instagram, it felt like Instagram, but it had video, and we didn’t. And that pointed out very clearly that Instagram should have had video.

A lot of people, with the introduction of Stories, look at our product and say, “Oh, they just added this feature from somewhere else.” But the fact that people are taking to it so quickly, and the fact that people are using it so much, makes me believe that they wanted this inside of Instagram for the longest time, and we just didn’t have it. And that’s a different way of looking at the same situation.

And the thing that it fulfilled was, “Hey, I’m over here in feed posting great photos that get likes, but I’m really trying to curate my life. But I’m lacking this ability to connect with those same people in a very informal way. And I can’t do it when you have likes and comments and I’m competing against celebrities in feed. But if you give me my own space—you give me funny, creative tools—if you let me express myself as much as I want—and by the way, I know it’s not going to last on my profile—like my personal art gallery—then I’m willing to do that.” And both of those things together actually is the product that Instagram is shooting to be.

How do you keep Instagram feeling like Instagram as it becomes deeper and richer and there are many things you can do in it, rather than one or two things you can do?

To answer that question, you first have to know what Instagram feels like. And what are the qualities that make Instagram Instagram. And those would be our values.

We typically focus on social innovation rather than hardware innovation. Rather than going around touting that, we have some new device or thing that flies—those are all cool, and very needed in the world. But what makes Instagram Instagram is thinking about how we can innovate on the social interactions between people. How we can up-end the norms of sharing and provide you with closer connections to people. And what types of innovations exist there.

I think Live, in the way that we did it, is pretty innovative. Live is ephemeral. And that’s not an intuitive choice for most people and companies. In fact, most companies that do live all have permanent recorded streams that then go on some profile.

They’ve been moving in that direction for the most part.

Yeah. Either ephemerality on Live is a bad feature or it unlocks a completely different kind of behavior. If you look at Top Live on your Explore page, you tap in, you see people hanging out. It’s not about producing content. It’s not a thing that lives on. It’s an interaction in the moment. And that’s a rich, human experience to have. When you tune in to Usher in his car listening to his music that isn’t released yet. Or you tune into a musician playing the guitar for everyone and taking requests. Or you tune into someone who’s just sleepy and tired and wants some company.

That’s what I mean by social innovation, which is it unlocks new experiences you wouldn’t have had. Rather than a device or something I can sell in a store. That makes Instagram Instagram.

What also makes Instagram Instagram is we try to do things in the most simple way. We don’t always get it right. But there are a lot of ways to introduce Stories on Instagram. We could have made a separate app. We could have taken over the home screen. We could have integrated it too much in feed, so that your Stories posts are also in feed.

But we just did the simple thing. And we designed a really simple bar, up at the top of your feed, that’s totally integrated into your consumption experience, that just works. And when we did that, we didn’t just blindly adopt a new format. We built on top of it. We allow you to pause. We allow you to go back. When you swipe forward, it’s clear that you’re going to the next one, because we have this cube animation.

In 2015, you did Layout and Boomerang, and they were separate apps. Was that unbundling a blip?

I’ve thought a lot about this question, because I get it internally as well. Which is like, “Which kind of company do you want to be? Do you want to be a unified mega-app company, or do you want to be a stratified satellite app company?” I guess I reject the premise of the question. I don’t think you are one or the other. That’s the wrong question.

The right question is, what makes sense for that app? For instance, let’s take Facebook, a non-Instagram example. Messenger is just categorically a better experience, as a separate app. You have a clean push notification channel. When you see the icon, the little red badge tells you exactly how many messages are waiting. When you tap on the icon you go straight to your unread messages. There’s no loading of anything else.

Instagram’s standalone Boomerang app lets you create GIF-like looping video clips

The question really is, when are apps better as standalone apps and when are things better built in? Boomerang, you want to open immediately to a camera, and you want to take a bunch of these, because you’re in a funny scene and you want to see what it looks like. And it’s just easier to access. And not everyone wants to produce a Boomerang.

We can, and we did, end up building it into Instagram as well. But it’s very useful as a separate app. Same with Layout. I don’t want to have to open up Instagram, load my Feed, go into the camera, select a bunch of images, create this layout, and then save it out. I want to just load up this app and use this specific tool.

The answer really is, it’s an “and,” not an “or.” We’ve shown success with Boomerang being built into Stories, for example, as a format. And it’s successful externally as well. It’s a marketing tool for Instagram, but I think it’s more useful for a lot of people as an external app.

As you’ve picked up the pace of how quickly you release stuff, has that required any basic changes to how you create products?

Every day is different. I wish I could tell you from my experience for the last four months of product innovation at Instagram that we now have a playbook that works. But what happens is that you get to the next four months and it feels completely different, because we’re working on different kinds of problems and different types of products.

I will say that the biggest thing that unlocked external product innovation and launches was staffing up the team. We went from a much smaller team to a much larger team fairly quickly. We were able to do that because we scaled our senior leaders as well.

Building out a senior team was probably the best thing we could have done for the company over the last year. And you just have more hands on deck to scale the people side of the organization. Because ideas, we have plenty of them. Being able to make them move and execute on them is a totally different world.

The other thing that changed internally was we stopped thinking on a marginal basis and we started thinking on a total-cost basis. Instagram Stories could have been seen as a risky thing to introduce. What argument might you make if you work here? You might say, “Well, what if everyone starts producing Stories and they don’t produce in Feed anymore? Right? But wait, all of our ads are in Feed, and what happens then?”

But the lesson I learned from watching Facebook make bets, and other companies as well, is if you worry about on the margin trading off, you miss the big picture, which is if you don’t have this other format, your previous format is worthless. Because eventually, people want both of them together. So you have to make the trade. Because on a total cost basis you’re actually way better off.

It’s basically the same problem that magazines with websites had. Did you stick with the magazine when it was wildly popular, or did you also do the website?

Yeah. It’s marginal thinking versus total-cost thinking. The second you ask yourself, “What happens if the value of what we have now goes to zero?”—not that it’s going to—but like, what if. Just play the hypothetical. What kind of decisions would you make? I think that unlocked a torrent of creativity inside. Because everyone saw our thriving business. Everyone saw our thriving feed ecosystem.

Do you give any thought to whether Stories becomes the predominant Instagram experience at some point? It’s almost coequal even now.

Wouldn’t that be interesting? I think about that outcome, although I’m not convinced that will be the outcome. It depends on how you define the dominant experience. Is it defined by how much time people spend, how much content they consume or produce, is it the value to the business?

An image from Instagram user @jonburgerman, who uses Stories for a unique form of photo cartooning.

There will always be a world where people want to express the highlights of their life, and save them to show them to their friends, their family, and to remember them themselves. But that does not mean that there can’t also be an experience that lets you share on the go the moments of your life that are exciting, but maybe for a day. That aren’t necessarily things that you want to hang on the refrigerator or the gallery wall. The sketches of your life rather than the paintings. That’s fine, too.

But if you’re a moments company, if you think about the world in terms of these shared experiences, then both of them make sense to build and maintain together. And there will always be a market for both of those.

Now, which one becomes most profitable, which one becomes the dominant time spent on your platform . . . Listen, I wish I was better at predicting these things. But what really matters is that we have a play in both. And by the way, the play in the new space is going very, very well. The last stat we released was 150 million users. And that was in five months. That’s crazy.

So yeah, things are going well. And all the thinking frameworks I just described, both the new mission and also thinking on total-cost basis rather than a marginal basis, allowed us to be more risk seeking than we would have been in the past.

I said “risk seeking.” But ironically, it’s almost riskier to not do it. And that’s not the way a lot of CEOs think, a lot of boards. It’s almost riskier to not disrupt yourself.

MAKING STORIES MORE INSTAGRAMMY

You’ve been refreshingly up front about giving Snapchat its due for the format of Stories. Right now, their Stories and your Stories have a lot in common, but it seems like they’re diverging at least a tiny bit in terms of features. Do you envision them being generally parallel over time or could they become quite different?

It’s up to the two companies and what they work on. In the past few months we introduced links into Stories for verified accounts. That’s a different feature that exists on Instagram that doesn’t elsewhere. The controls back and forth actually ended up getting adopted back into Snapchat. It’s good for innovation to push the format forward. And to try to dream up new ways that it can be used, and adding features to it that are unique means that we’re all pushing the format forward.

The best analogy would be newsfeed on Facebook. That was a big innovation at the time. And all of a sudden, other companies realized, ‘Yeah, in fact, that’s a really useful way to consume changes on a network. And Twitter wouldn’t exist without that same concept. LinkedIn uses it. Name a single network that doesn’t use it. I think maybe Snapchat is the only one.

You have these formats, and then it’s up to the individual company to then innovate on top of it. And I think you’re seeing that. It’s only been five months. These things become more apparent in time. But true innovation is what you do on top of these formats, and that’s going to be interesting to see play out.

How important is it to Instagram that young people continue to think of it as being cool and belonging to them? I went out to dinner with some people last night who were 50 and up, and they talked about it in the context of being important to their kids.

I’ve never heard the criticism that Instagram feels too much for one demographic. Whether that is an age demographic, like “Oh, it’s only for teens,” or “Oh, Instagram is for old people.” I’ve never heard that. Except for maybe the first few months of Instagram existing, that it was for hipster photographers, right?

You’re definitely past that.

As a self-proclaimed hipster photographer back in the day, that was the one criticism. But then we opened up the explore page, and one of the countries we took off in was Japan. And you saw all these people from Japan posting on the Explore page who didn’t fit that caricature of an Instagram user.

That shows that we were so universal from the start because we focused on that shared experience that we could unlock between two people.

I don’t worry specifically about being cool. [Long pause.] But if you ask, “Is cool another word for useful?” Then sure, I want to be really useful for each and every person. And if we’re not useful, then I think we’re not doing our job.

Speaking of celebrities, can you talk about what the role is of following people who I don’t know? You mentioned Usher. Is that different than what you’ve been talking about in terms of connections with friends and family?

No. It’s easy to take what I’m saying and only focus on the shared experiences between you and loved ones. But let’s actually take a more controversial example, which is businesses.

When we talked about this mission internally, the first hand that went up was like, “Wait. I work on our business team. What does it mean to have a shared experience with a business?” When we were forming this mission internally, I said, “I really don’t want to shoehorn in businesses into this. I want people to be clear that shared experiences can be with businesses as well.”

And I asked people, “Do you have businesses you care deeply about, the same way that you care about a friend? Maybe not exactly the same emotional level. But do you have a passion for specific businesses?” I think a lot of people in Silicon Valley feel that way about Apple.

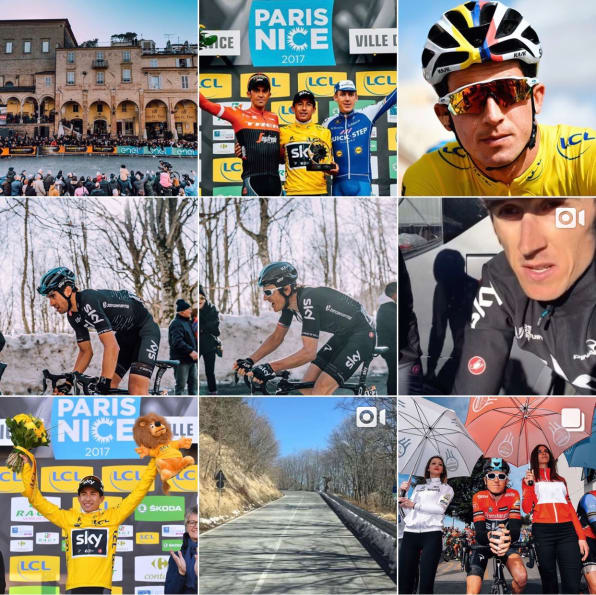

I’m a cyclist. I feel that way about Rapha, which is a cycling clothing brand. I feel deeply about a helmet company that I really like for cycling. A company that makes the components of the bike. I love these companies and I follow them. And I care when they release a new product and tell me about it. I care when the cyclist that they sponsor wins the Tour de France and I get to see their thoughts on that on Instagram. I care when I follow Team Sky. They’re arguably the top cycling team in the world. And they’re on Stories all the time, posting from their first tour of the year, the Tour Down Under in Australia. And I’m seeing them warm up, I’m seeing their stage races, I’m seeing the athletes after the race.

Images from Team Sky’s Instagram feed.

Celebrities fit into this as well. It’s cool to see, from a celebrity’s perspective, them walking down the red carpet of an awards show. Going live, or telling us how they’re feeling when they’re nervous, about to go onstage. Those types of experiences bring me closer to an otherwise, historically speaking, not very close relationship that was managed and dictated by tabloids or the paparazzi. But now I’m connecting with these people individually. And that makes Instagram stand out in terms of the platform, because it’s one of the only places you can really do that, in an authentic way.

MONETIZING MOMENTS

Speaking of companies, I looked at an interview we did with you in 2013. In it, you said that Instagram might get serious about monetization when it reached 700 million users. I’m not sure if you chose a random number. But you’re essentially there. Can you talk about where you are with monetization now? How far down the journey are you?

I would love to remember exactly my rationale to say that.

You actually said 70 million or 700 million. You picked a large number at the time, and an incredibly large number.

When we pitched Instagram to venture capitalists early on, it wasn’t about photo sharing. It was to be a business someday, too. A sustaining business that can achieve its mission. And the best companies are not just companies that have an awesome vision and mission, but one that can in fact support that mission with a sustainable business that allows it to reinvest and grow, and therefore be more successful at attaining its mission. And that’s what I wanted to create. That’s what Mike [Krieger, Systrom’s cofounder] wanted to create.

And the idea was, how do we create that in a way that meshes with the experience on Instagram? It turns out that a great business model is to go to companies who have budgets to connect with new consumers and build a product that charges to connect with new consumers. And by the way, if we’re super-relevant—meaning the ads are very relevant—than it feels like basically lead generation for new potential shared experiences and relationships you can have with brands. And that vision has come true over the past couple of years.

We started out very slowly. We were very meticulous about easing into it, about understanding what the community thought. And then we pushed on the gas as soon as we found the model that worked, which was hooking up into Facebook’s system. And counterintuitively, the more advertisers you have in the system, the better the ads get for each individual person in an auction-based system. You have more candidates to choose from, so if your specific interest is in fly fishing, we can serve an ad that relates to that interest. It means advertising qualitatively gets better.

It’s still in the early phases. Facebook is a very large company. But it’s looking really promising, which is exciting.

You moved quickly to bring ads into Stories. Was that a conscious decision based on the fact that Stories got large really quickly?

The model internally is always show consumer engagement first and worry about monetization as an afterthought. In this case, I saw two things. One, it’s very large, very quickly. It’s not a tiny feature. The second is, advertisers really want more immersive formats to reach their consumers.

We have a great feed product that works really well. But there are lots of advertisers who are like, “I wanna do something fresh and innovative and interesting.”

We didn’t push a bunch of advertising into Stories yet. Today we’re doing some beta tests. It’s a limited set of partners. Same thing we did with Instagram feed. And guess what? We’re going to learn from it and we’re going to see what those advertisers like, dislike, we’ll learn what consumers like, dislike. We’re going to refine the model. So that eventually, one day, when it is ready it can become a big business, in the same way that I think we did it correctly in feed, I think we can do it correctly in Stories.

BEING PART OF FACEBOOK

When I chatted with you for my Facebook story, you talked about how Mark [Zuckerberg], Sheryl [Sandberg], and Shrep [Mike Schroepfer, Facebook’s CTO] were essentially like Instagram’s board. Is that still the right way to think about that?

Totally. I love when people come to the Instagram campus, because not everyone realizes how autonomous we actually are. The great thing about Facebook is that Facebook, Inc., is a collection of companies, all of which share a similar mission, to connect the world. Ours is a specific version of that, which is to strengthen relationships through shared experiences.

And when you come to the campus, you realize that all of these companies link together to push that larger mission forward. Each of them have their own personalities and vision. And when you walk into the office you realize that we have different cultures as well.

But the superpower of each of these companies as part of Facebook Inc. is that you get to lean on some of the most experienced, intelligent, and thoughtful people in the Valley to push the company forward.

I don’t think Mark sits on any other boards. I know Sheryl is on Disney’s board. But my point is that you get these people who, if you were an independent company, you’d die to have give you advice, and you’d die to have help guide your company. And we get the best of both worlds. You get input and you get guidance, but you also get pure autonomy, and you get to push your vision forward, which also happens to push the larger company’s vision forward as well.

How much time do you spend thinking about Instagram’s place within Facebook’s greater aspirations and goals—both business goals but also cultural goals?

The deal I made with myself is, as long as the missions are linked and I focus on that mission—the mission that we defined, that I’ve repeated a bunch of times—then everything works its way out. And I believe Mark feels that way as well.

Obviously, we coordinate, and we think about tactical goals together. But 99.9% of my time is pushing that mission forward. And the side effect of that is that we end up helping Facebook, Inc., as well.

Mike [Krieger] once told me that from a technological level, it was fantastic to have access to the Facebook stack but you were not boxed in. You were able to make your own decisions. Is that still correct?

Totally. Product-wise, it’s super autonomous. And what’s more interesting is that at the same time, we’re able to plug into an infrastructure that scales.

Now to be fair, we were doing that before with Amazon [Web Services], like many startups do. Maybe it’s more of a comment about how startups today, or companies, when they build infrastructures, can support the companies within them, and also can decide to support companies outside. Some of the other companies in our industry don’t even have their own infrastructure. They lean on Google and others to scale.

That’s probably the biggest difference between today and maybe like 10 years ago in the startup world. And it’s part of why you see such rapid acceleration of ideas and expansion of footprint. Because a lot of the things that were very, very difficult, the technical difficulties of scaling, have been abstracted away. And companies are thinking more and more about product innovation and building great consumer experiences.

It’s not to say that the technical side isn’t hard. We actually have very large teams at Facebook who make this stuff work. Without them we’d be nothing. It’s just to say that as a company, as Instagram, we get to focus mostly on product innovation. And that’s my passion, so I’m glad I get to do that.

LIVE VIDEO AND BEYOND

When you launched live video, were there technical challenges to do that, or was it more of a design challenge? And is that based on Facebook’s live video?

I remember on launch day walking in, and I was like, “I don’t recognize a bunch of these people.” And they’re like, “Oh yeah, that’s the Facebook Live team.”

What’s cool is that these teams came together to then launch a product. And the reason why they came together so neatly is because they had a shared mission. Like, making live video a format that people see, watch, and find useful is a Facebook mission thing—not a Facebook thing, not an Instagram thing. And we each do it in our different ways. But the teams come together around these shared missions and make things possible. If they hadn’t done all the work to make the infrastructure sound and learned a bunch of lessons because they were out before us, then we wouldn’t have been able to launch so smoothly.

Will you ever reach the point where it becomes difficult to stick new functionality in and still retain the simplicity?

[Long pause.] Yes, if we don’t retire things that don’t work. But we also have a history of retiring things that don’t work.

A simple example is removing Photo Maps from the profile. It just wasn’t a popular feature, it took up space, took up code complexity. And we were able to remove it somewhat seamlessly and retire it, and that made room for other stuff.

You evolve your product. And evolving means removing things that don’t get used or aren’t perfect and changing things that exist into new formats. And then adding new formats. But one of the things that makes Instagram special is that we focus on simplicity.

Hopefully I won’t let us get to a point where we have too much in one app. I pride myself—and I know we pride ourselves—on making Instagram feel simple, direct, and to the point. But the second you start serving hundreds of millions of people, there are a lot of use cases that come that you didn’t have when you were serving 30 million people. [Laughs.] It’s always going to be a tension, but it’s one that we’re actively managing and aware of.

–

This article first appeared in www.fastcompany.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +9714 3867728 or mail: info@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com