Architecture that morphs, clothing made of woven LEDs, and interfaces hidden in everyday products

For years, experts have predicted that screens will disappear, as voice interaction and ambient computing take over. But London-based digital design studio Universal Everything thinks screens will stick around—they just won’t look anything like the ones we’re familiar with today.

The studio’s project Screens of the Future teases a series of futuristic products and spaces embedded with interfaces. Each concept, illustrated in a 10-second video, is rooted in emerging technologies like flexible displays and shape-shifting materials, and provides a concrete—if often far-fetched—example of how screens might be used in daily life in the future.

Universal Everything is best known for its CGI and entertainment design, from 3D data visualizations to trippy app that accompanied a Radiohead album to the mind-spinning visuals of Coldplay concerts. Inspired by the studio’s research into displays and briefs that have come across their desks, this latest project skews more conceptual than practical—though it remains a tantalizing glimpse at the radical future of screens.

Interfaces could be so thin, we’ll be able to affix them to biological material.

This concept imagines a screen made of gel that’s applied to the side of your pet goldfish, relaying the health information of the fish. At best, it’s a silly idea. Your fish does not need a health tracker. At worst, it’s potentially dangerous for the fish. But the insight that biological materials could be combined with screens is promising and may one day be possible, given the rise of bioengineering. Another concept in the series suggests similar potential—a screen as thin as a film that could coat the leaves of a plant and show basic graphics that correspond with data from the organism. A version of this already exists: MIT has developed a temporary tattoo that functions as a custom, wearable circuit.

Building facades could be made of moving screens.

This interface imagines buildings with exterior surfaces that morph and react to their environment. In the animation, physical pixels animate the entire wall, creating real movement along the building’s surface and even forming a functional element: a stairwell that emerges out of the blocks. This concept is fast becoming a reality: morphing buildings, like a rotating skyscraper slated to join Dubai’s skyline in 2020, are already on the horizon.

Screens will be woven into the clothes we wear.

Clothing that adapts to its environment is still largely experimental (and sometimes gimmicky). Think about Marchesa and IBM Watson’s “cognitive dress,” or this 3D-printed cape that reacts to the gaze of onlookers. Adaptive clothing may be the future, but it will likely be more subtle than the examples we’ve seen so far. Consider textiles woven with LEDs to create clothes that can display different graphics. Another concept from Screens of the Future shows a dress that changes based on its surroundings, flashing from pattern to pattern as the wearer walks in front of brightly colored backdrops.

Screens could take the place of traditional architectural elements.

These columns initially appear to be traditional architectural features, until they start spinning into a swirling mass of colors and shapes. They are actually three sculptural screens that have become integrated into architecture as a decorative, playful element. Hughes says that Universal Everything is getting pulled into architectural projects earlier and earlier to integrate screens into the fabric of buildings, a trend he believes will only continue. Brands seem to think that this kind of space is more appealing to consumers and perhaps makes them appear more cutting-edge and futuristic. Hughes believes we’ll see an even greater influx of screens as architectural elements in spaces like malls, galleries, cultural spaces, corporate offices, and flagship buildings.

Screens could become dynamic elements of products.

What if everyday objects were embedded with dynamic, moving interfaces? In this concept, a CD’s plastic box plays music, while the box morphs its shape and color to form an abstract art piece. The idea is to create a more visual form of music, where data from a song is transformed into art in its own right. But it also indicates a future in which screens are integrated creatively into everyday products. The screen becomes a dynamic element rather than the static, touch-screen interface we’re used to today.

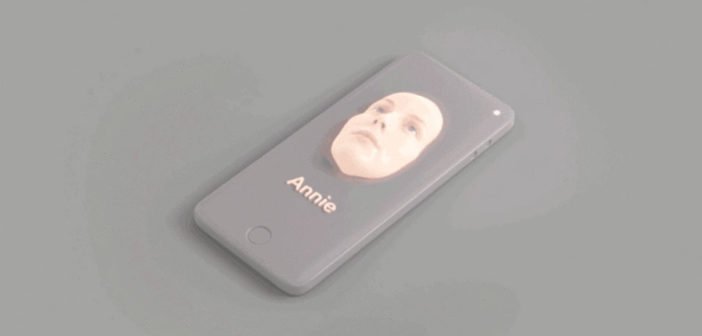

Screens could take on three-dimensional qualities.

Universal Everything imagines a 3D future for screens. Right now you might scroll through a list of names to find a contact you’re searching for, but in the future, contacts might pop up as 3D faces that protrude from the surface of your phone. (Reminiscent of the creepy Hall of Faces in Game of Thrones, this interface idea descends a little too far into the uncanny valley.) But the same idea could be used to power a next-gen Google Maps: the phone could morph into a 3D map of a cityscape, helping orient the user.

Interfaces could have literal faces.

This creepy, colorful blob is meant to be a house-sized wind farm—with two eyes and a mouth. When it’s windy, the structure’s face turns into a grin; when there’s less wind, it looks sad. It’s a goofy but effective way to quickly convey how much wind there is. We’re already seeing home robots with faces and names meant to make them seem more human (but not too human). As artificial intelligence creeps into objects and designers give them personalities,interfaces—like the exterior of this wind farm—could be emblazoned with faces as well.

–

[All Images: via Universal Everything]

This article first appeared in www.fastcodesign.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +9714 3867728 or mail: info@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com